- Home

- K. M. Kruimink

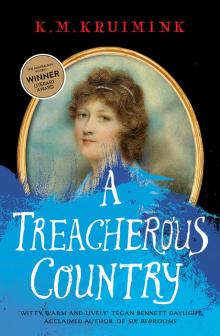

A Treacherous Country Page 3

A Treacherous Country Read online

Page 3

He inclined his head but, again, did not press me for further detail.

Ah, Susannah Prendergast! I took out her miniature, in its little gold case, and looked upon her for a moment. Perhaps I did this rather ostentatiously, with a romantic sigh, to prompt my Cannibal to ask me about her. But he did not.

The Artist had not possessed any green paint, and so painted-Susannah’s eyes were rather greyer than in reality, but aside from this, and the fact that no painting could accurately portray the Vividness of her glance, the delicate blue veins at her temples, and the little seashells of her ears, it was her exactly. Indeed, it was amazing how like her it was, given that I had been compelled to pay the (Catholic) Artist to attend our (heathenish) Church of England to make some discreet sketches in the pews. For I should not have suffered the embarrassment well of asking her to sit, and being denied.

Where did my thoughts take me when I beheld Susannah’s likeness? The little picture was eloquent upon the subject of beauty, and all the good things tacitly understood to accompany beauty, whatever they were—honesty, perhaps, and charm, and wit, and other such things, I supposed. And Susannah herself? I thought of her as I had first seen her, in a pink dress with little golden flowers to match her hair, engulfed by the white-and-gold divan, when Mrs Prendergast had brought her to be introduced. There had been a frailty to her as she looked around at us. She had not said much, which, I suppose, was moderately correct of a girl so young. Still, she had not done well on that occasion, I am afraid. I was only glad Father was absent. She had worn quite a sorrowful expression upon her face, until Mrs Prendergast twitched her eyebrows perhaps one-tenth of an inch in a certain subtle way. At this signal, Susannah had started a little, and changed her expression, smiling, and looking wildly about the room for something upon which she might rest her glassy eyes. They fell upon the Chinoiserie cabinet and there stayed, and so she smiled desperately at this cabinet for some duration of time, wrenching her gaze away with visible difficulty when Mamma addressed her directly. Poor girl! Mamma had been kind.

Later, Mamma had spoken of her with a view to my middle brother John, but it was decided he could certainly do better, even if she came with money.

I thought of Susannah as I had last beheld her, looking grave in a subdued gown, almost as if she were in mourning. She was quiet on that occasion, too, but was in much greater possession of herself—perfect possession—saying little but a courteous farewell.

I do not mean to suggest that she never spoke; she spoke a great deal between those two times. Those two images I have of her, the first and last I had seen of her, I suppose do nothing to represent the person herself. Sometimes I had wished I could see through her white forehead and into her brain. If only I could read her thoughts, unfiltered by the many layers of politeness and convention through which we communicated! Sometimes she would sit with her hands clasped tightly together and listen to me with an air of impatience, as though she were eager to disagree. She had had a greater range of experience in life than my own, despite being a little younger—only now was I advancing upon her in that regard. Her mother was dead, and her father was in Burma, we were told, and he had tried to keep Susannah there, and found it most unsuitable, and thus she was sent to make her life with her great-grandmother in Norfolk.

A million worlds away, my Cannibal and I crested the rise, and there before us was the village. This place had the hastily erected air about it many such habitations do in the colonies, like a stage-set, and yet there were people going hither and thither with the same easy purpose just as they might in my own ancient village at Home.

The houses varied to a degree in size and profusion of chimneys, but all were stone or brick, and neatly kept on good, large plots of land. Indeed, they were oddly spaced one from the next, if one were to compare with an English village. It was much as if the inhabitants of the houses were feuding with their neighbours, and distanced themselves accordingly.

It seemed less cold amongst these signs of civilisation. After our long morning, it was a comfort to exchange quite ordinary nods with quite ordinary-looking country folk, although the wood smoke made my eyes smart, and there was one less-ordinary-looking countrywoman with a jaw like a brick and a bosom like a man-o’-war whose fierce aspect rather made me wish to retreat all the way back through the colony and across the seas to my childhood bed in Norfolk. The great, green hills swept upwards all around us, and the broad river glinted ahead. Upon one hill nestled a white church, and on another a brown.

The houses gave way to the Establishments of the village, which were larger and more plentiful than I might have expected: there was a General Store and Post Office, and a Dispensing Chemist’s, a Bakery, a Butcher’s, a Draper and Haberdasher’s, a Saddlery, and a Bank. All were free-standing, with large, glass-paned windows, and oil lamps above these windows to illuminate the displays at night. The culmination of all these fine institutions was the Hotel. It was called the Royal, which was, let us say, an exaggeration. Nevertheless, it had a sufficiently pleasant aspect, and I cast yearning eyes towards it.

The Bank had given me pause. My first thought was that I ought to go within and withdraw some money against my letter of credit. My second thought was of my Cannibal’s preoccupation with the treachery of the road. Weighing the matter, I decided I had best make do with the few coins I had about me, and wait until my return to the relatively more civilised Hobart-town. There, at least, I might take a room in a more habitable Establishment than the sink-hole of the previous night, which might have a safe, or, at least, a door with a functioning lock.

My Cannibal hailed an old man resting himself on a bench outside the General Store and Post Office, and they exchanged some words too rapid and particular for me to discern. A boy driving a sheep came along the road, and he either did not see me or did not care to see me, for I was obliged to move Tigris from his path. A surpassingly pretty girl with fair hair emerged from the Draper and Haberdasher’s with a parcel clutched in her hands. I tried smiling at this individual; she did not look at me. Two plump matrons with various infants about their persons were engaged in serious Discourse outside the Chemist’s. As I rode by, I heard one say to the other: ‘There is nothing so good as soap and water, and old-fashioned elbow grease—and no Concoction will convince me otherwise.’ A very small hand waved in regal fashion to me from somewhere within its mother’s dress, and big eyes under fairy-down hair looked out. ‘What is more,’ the woman went on, ‘I do not trust his expensive prescriptions, when everybody knows all a sick baby needs is a little bread soaked in wine, and some sago.’ Her friend was nodding and grimacing in profound agreement. In all, this was a village with Life and Liveliness about it.

As I paraded along the thoroughfare upon my black steed, I found that the Royal Hotel was apparently Magnetised, for it was drawing me in by the stirrups.

Even in the face of my man-eating hunger, I paused for a moment to gaze beyond the Hotel at that silent river. I could see the broad and drifting surface troubled with reflected trees, clouds, and the stone arches of the bridge. The water was dark, like tea, but not tea, or whisky, or watered-down ink—but it had the air of freshness about it, and it glimmered like something that had lived many millions of years ago, and now had distilled into something rare.

‘You advised me of your hunger,’ said my Cannibal, who, I saw, had paused, and stood regarding me. ‘And I advised you of our need to press on. I shall leave you to choose your own action next, as you, like me, are one of the Free, and may do as you wish.’ And he strode away, towards the bridge, without further ado or farewell.

Perhaps public houses are the secret of Life. I know the map of my own life can be signposted by public houses.

There were two mounts tethered already at the trough by the steps, a very fine grey stallion, and a dear little grey pony. A boy lounged against the bottom step. Now there is a Law of Nature worth investigation!—the ubiquity of a particularity of child who, by virtue of some no doubt Scientifica

lly measurable confluence of poverty, dimples, freckles, impudence, wit, selfishness and charm, can only be called an Urchin. I must make a note.

The Urchin in question said, ‘Leave her here, sir. I shall watch her.’

‘Thank you, my lad,’ I told him, and, dismounting, gave him a penny from my pouch.

I saw my Cannibal looking back at me from the middle of the bridge. He raised a hand in wry salute and I, proudly, hailed him in return. He was correct; I was one of the Free, and would do as I wished, and I wished to take a good meal and pass a comfortable night before going forth to find the floating Platform or whatever the whaling-station might in fact be.

‘Penny don’t buy much these days,’ the Urchin said. ‘Economy as it is.’ He gave a manly shake of the head. ‘Wool price down, sir. Read in the Colonial Times.’

Mark: the land where Urchins read the news-paper for tidings of the Economy like the soberest of chaps!

‘I shall give you another when I return,’ I said.

‘Fanks.’

Tigris made no objection to my tethering her to the post; she immediately occupied herself by drinking the water in the trough.

‘What happened to her?’

‘What do you mean?’

‘She’s all patchy, sir. All patchy.’

‘Well, never mind that,’ I said. ‘I am so hungry I feel quite faint.’ Urchins respond to nice, brisk candour from their betters.

‘Go and have a bite to eat then, sir. Not the rabbit pie,’ he added. ‘It ain’t rabbit.’

‘Oh—thank you.’

‘’Nother penny, sir,’ he said. ‘Advice don’t come cheap neither.’

‘I shall give you your balance when I emerge, and it shall be dependent on the usefulness of your advice, and the safety of my horse,’ I told the little lad. ‘I have counted the bald patches; there are seven, and I do not wish to come out and find more.’ Now that was a silly remark. What was I suggesting? That the boy would pluck hairs from Tigris while I was indoors?

I mounted the steps quickly, to escape my embarrassment, then immediately returned, and removed my harpoons from where I had lashed them, and again climbed to the door, harpoons over my shoulder.

And there was a homely place! An image of the Gaol of a Hotel I had passed the previous night in, with my Prison Cell of a room, and Torture Device of a bed, went before me. With this array of horrors in my mind, I might better enjoy the comforts of the Royal, by contrast. Royal it was not, indeed, but there were honestly worn carpets upon the floorboards, and large windows pouring honeyed sun—where they had contrived to find honeyed sun on such a clear cold day, I did not know—into the tap-room, and a fire crackling merrily in the great hearth. The room was taken up with two convivially long wooden tables running almost from the far wall to the bar. Surely the village entire could be seated at such mighty boards, although that afternoon they were unpeopled but for one dishevelled man propping his elbow by his glass.

A woman of indefinable age—the sort who might be thirty-five or fifty-three—leant upon the bar, stout and red, as a proprietress ought to be. Beside her was an aged farming-type with a pipe poking out from amidst his respectable grey beard. The proprietress was making some concession to work, with a rag bunched in her hand, but was waxing lyrical, gesturing with the rag in the air to punctuate the following remark: ‘And I recalled,’ twas not the twill, but the tweed!’ This induced a great shout of laughter in the farmer. He removed his pipe in order to make the exclamation of mirth, and then soberly replaced it.

‘Oh, good afternoon!’ the proprietress called to me. ‘Come in, sir. Warm yourself. It is cold—I was only just outside myself. This morning’s frost still has not cleared.’ I had the sensation once again that the entire village was the set for a play, and these two had been posed and ready to begin a rehearsed show upon my entrance.

There was a velvety old armchair by the hearth, soft with a thousand pairs of buttocks, a relic older than the colony itself. I dropped myself there and rested just as my Cannibal had been when I first beheld him. It was true I felt a sense of unreality, but the chair’s threadbare upholstery had subsumed the heat of the fire, which transferred back into me, and that was real. I felt a suffusion of nostalgic comfort so strongly it made me a little sad with the general longings of lost childhood one feels in such moments, especially as the proprietress had spoken in the unmistakable accent of Cornwall, whence had come my childhood nurse, as well.

Nurse had been amazingly unable to peel an apple with any delicacy, and from a robust red apple she would present us with a few poor porcelain-thin slivers of apple-flesh to eat. I remember my own mother taking the paring knife and the apple from Nurse’s hands one picnic, upon witnessing the destruction and travesty of Nurse’s attempt, and peeling the apple herself, the skin dropping in one great curl in her lap. There was then a game with the apple peel, in which the peel was dropped in a certain way, to fall into the initials of my future love. It was all Cs and Os, as one might not need a Mystical Nature to divine apple peel might naturally fall, although that was significant for Freddie, because of Charlotte Oxford.

‘What is it you shall be taking, sir?’ the proprietress asked me, abandoning her old friend to come and loom benignly. She wore her brown shawl crossed over her bosom and her hair in a discreet cap, like any good country-woman at Home.

‘Have you kangaroo steamer?’ I asked.

‘No, sir. I am sorry, but I do not touch kangaroo-flesh. I was compelled, when first I came here, to eat more of it than I should ever have cared to. We do have rabbit pie, which is especially hearty to-day, white bread and cheese, bacon, cutlets, pork twice-laid, rum, gin and ale—and cider aplenty.’ She went on to list some other comestibles, but I struggled to pay her any attention, so great was my hunger and so deep my weariness.

So lulled was I by the warmth of the room and of the welcome, and the ‘especial heartiness’, that I asked for rabbit pie and cider, despite the Urchin’s word of caution.

As if to confirm the goodness of the place, the old farmer puffed a smoke ring directly over his bald head and sat gazing beneficently at me with the ring floating above him like nothing so much as a halo. The other man, the down-at-heels man who was seated alone at one of the tables, took a final swig of his dregs, then rose and left.

‘Where are you going, Beasley?’ the farmer called after him, but there was no response. At least, there was none that I heard, as I leant back and drifted almost instantly into a dream in which I plunged through a sea of rustling leaves and saw a circle of pained white faces looking everywhere but at my mother.

I HAD ALREADY BEEN FORGOTTEN

The proprietress told me she did not wish to wake me, and thus woke me. With a hearty and humorous kind of servility, she brought me to sit at the bar to eat, placing me a polite stool or two away from the farmer.

A pair of neatly dressed girl-children came into the Hotel with a pot to be filled with beer for their father. They were very similar in looks, although one was taller, and the other had a livid purple birthmark on her face. The proprietress tended to them, and sent them off, saying sternly, ‘You tell that man to make it last, for I do not wish to sell him more to-day,’ which seemed rather counter to sound business practices.

All the while I devoured the pie she had brought me with a relish probably disproportionate to its simplicity. I thought of the Urchin’s warning against this fine pie, and scoffed, and resolved he should not have another penny for his bad advice.

The proprietress and the farmer had evidently consulted quietly together as I slept, for next they put to me their guess as to my Purpose in their valley. They told me that I was a farmer myself, seeking a parcel of land to buy, and that although I spoke rather better than a humble farmer (they said), all men were equal here, except for those who were not. I was a gentleman farmer, they told me. Well! I was in luck, for it happened that they knew of a family with an established wheat farm which they wished to sell (at a fair price) in order

to move north to be nearer their kin in Victoria, and were mostly not criminals (the local family or the northern kin or all involved, I was not sure). The farmhouse was without rival in the valley, and had a staircase imported from Italy, which was greatly admired by all who saw it. And Gentlemen Do Love Bread. This last said with some meaning.

‘Everybody is selling something, here,’ I said.

‘The Economy is taking a downward turn,’ the farmer said. ‘I sold my sheep two, three year ago. Got in early.’

‘Mr Green read the Economy in the clouds,’ said the lady-publican. ‘Now he is very comfortably Retired—if you do not mind my saying so, Mr Green,’ she added, as an aside.

‘I do not mind you saying what is true, Mrs Nancarrow.’

‘Perhaps the sorry state of the Economy is why I cannot sell my harpoons,’ said I.

‘Yes, we did pass a few moments in trying to guess why you carried those,’ she said. ‘They do not speak to you being a farmer, although the look of you does.’ She and the old man exchanged a glance rich with meaning.

‘There is little future in whaling here, my lad,’ Mr Green told me, leaning closer.

‘Indeed. We have heard the whales are either dying in excessive numbers, and not replenishing themselves, or, at least, are no longer presenting themselves to be hunted,’ said Mrs Nancarrow. ‘Foolish creatures.’

‘’Tis a great pity,’ said Mr Green. ‘It was a mighty trade.’

‘You see how the Economy is beset from all sides,’ said Mrs Nancarrow to me.

‘Wheat, oats and barley, and apples, in the south,’ said Mr Green, and I saw again the skill of my mother’s hands as she peeled the red fruit. ‘And cattle, perhaps. That is the future.’

‘And timber, besides!’ said Mrs Nancarrow.

‘That is true. Timber is also the future.’

A Treacherous Country

A Treacherous Country