- Home

- K. M. Kruimink

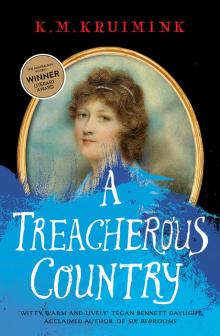

A Treacherous Country

A Treacherous Country Read online

K.M. Kruimink was born in Tasmania and spent most of her childhood in the Huon Valley, with an interlude on the West Coast. After completing a largely ornamental Arts degree at the University of Tasmania, she lived and worked interstate and abroad for several years. Today, she lives once again in the Huon Valley, now with her husband and daughter. A Treacherous Country is her first novel.

First published in 2020

Copyright © K.M. Kruimink 2020

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to the Copyright Agency (Australia) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Email: [email protected]

Web: www.allenandunwin.com

ISBN 978 1 76087 740 8

eISBN 978 1 76087 395 0

Set by Bookhouse, Sydney

Cover design: Sandy Cull, www.sandycull.com

Cover images: Heritage Image Partnership Ltd/Alamy Stock Photo and Shutterstock

For Omes, and for Mum

CONTENTS

You with the look of the lost

You told me we would be eaten alive

I had already been forgotten

Perhaps I am an honest Vandemonian

I have become quite lost

Measureless to man

I resign

No one will give me a straight answer in this place

I am not claiming we are Princes

Our last Balloon sadly caught fire and then sank

It was never thus

You are sorely in need of a making

My beliefs do not control the Universe

The most wretched wretch of all

That is a sensible conclusion

YOU WITH THE LOOK OF THE LOST

How came I to a place like this?

What spirit drew me here?

These and other questions perplexed my mind on that day’s ride north from town. The clouds drifted and the wind blew, as clouds and wind will do. My breath was white in the cold air, and my horse plodded, and when I threw an apple core, it made a nice arc and subsequently fell upon the earth, just as you might imagine. Why, then, if all around me was evidence of the expected natural laws, did my thoughts not remain inside the privacy of my mind, but instead spike up out of my head and my eyes into points of interrogation? Why did I have the profound conviction that I was on the very brink of some discovery of the utmost strangeness? Why did I feel that in the next moment I should find the woman with the tail of a fish, or the fountain that would give me life eternal, or the sherry that would make me sober?

My Cannibal said he did not know. Perhaps he did not care, sauntering along with his thoughts firmly packed into his skull, impenetrable beneath all the hair.

Every time I blinked my eyes, a sea of huge bodies writhed inside my eyelids. Therefore, I stared hard into the bright sharp air, tears bulging in my eyelashes.

I had seen many animals die, but never a man.

I had never wondered if a person can be measured by an absolute value, or if all our qualities, good and bad, are modulated and by degree. And to what degree I myself achieve goodness, and to what degree I fail.

These were the things I ought to have been making into questions. But the eyes with which we look back upon our lives are clearer than the eyes of the moment, I suppose.

A slow sweep of rain moved over us. Behind it, the sun was weak and distant. The season was mid-winter, they told me, and it was indeed cold, although the month was July. All around were leaves flashing like schools of silver-green fish, on trees whose bark rushed and curled like running water.

Here is another question: can the season truly be called winter, if it is at the wrong time of the year, and the leaves have not fallen? Surely it is not winter, but some other thing entirely! It is not very Scientific to point to one thing and declare, Behold, it is cold, and then to point to another, and say, Behold, this too is cold, and conclude that these two things, which in all other respects may be entirely dissimilar, are necessarily One and the Same, based solely upon temperature! There are many things that are cold and not the same. A snowdrift, the sea, a shudder, a fish, metal, rejection. The Lieutenant-Governor ought to have thought of this, or at least have been told. He was a man of Science, I had heard, abreast with the changing times.

I put this to my Cannibal. He said the days had grown shorter, which is also a characteristic of winter. And that it was a good time to plant cabbages.

Tigris was walking dully, her head down. I had bought her before sunrise that same morning from a German man in a green gabardine coat, who conducted his business in an alleyway behind what he told me was an excellent local brothel. The mysterious light of his Argand lamp and the stench of its black oil had overpowered me, weakened as I was (for I had had no breakfast), and momentarily suspended my knowledge of the buying of horses. And whilst I do not know that any German has heretofore been called exotic, his accent in that moment had struck me as such. It was with a mind thus caught up by these various stupefying influences that I had first beheld the mare, and so she had seemed truly marvellous. She was like a horse cut out of the night sky, throwing a rippling shadow against the brothel’s brick wall, gazing beyond me to Elysium with eyes like enormous drops of ink. A Grecian beast, worthy of an Odyssey such as mine!

‘Tigris is not a Greek word,’ the German had told me. ‘The tackle is included in the price,’ he had added, casting a searching look along the alleyway, as though he should rather be elsewhere.

I am afraid the animal had grown rather less impressive as the day wore on. There had been a distinct aroma of boot polish about her that morning in the alleyway, which the German had told me was a kind of saddle oil peculiar to the colony. This aroma had caught in my nostrils and troubled me all morning, for I slowly grew to understand it was, in fact, boot polish, as it was gradually rubbed away from certain areas where it had been smeared to hide the horse’s bald patches. Now, in the rain, a slow tide of black polish crept inevitably towards my white gaiters. These imperilled items were new; I had purchased them in Sydney-town, and I did not adore the notion that their smart martial look should be besmeared as the result of my own innocence.

For a while this brought me very low, for such deceit was nothing less than cruel Extortion, to my indignant way of thinking. I yearned for Pharaoh, my barely tamed bay stallion at Home. O, for some spirit and a tossing head! I resolved several times over to dismount and set Tigris free, leaving her to wander off into the forest and find the Fountain of Youth and live forever mediocre, locked into the attic of her own mind. For not only was she ugly, but she was also Stupid. I had tried to offer her my apple core, leaning over her neck, but she was so taken aback by my arm appearing before her that all she could manage was an ungainly shuffle in the midst of the road and then to resume her latter plod, ignoring the apple core entirely. As we trudged on, however, the extreme vicissitudes of my feeling eventually found the midpoint where they habitually settle, and I kept the mare with me. She was unimpressive, it was true, but she was a tractable creature. She went forth with dumb conviction, her flanks warm, following my Cannibal along a meditative road overhung with trees.

‘Why is she called Tigris?’ I had asked the German.

‘Because,’ he had replied, ‘the sire was called Lake Hazar.’

I did not know what that meant, but I did not ask—nor, indeed, did I make any of the usual pertinent enquiries when buying a horse. I paid him the sum he asked without bargaining, although it left me with very little ready money; in short, I paid for gold and got brass.

Leaves like scimitars carpeted the road.

I clanked as I went. My Cannibal, padding along in boots so moulded to his feet he and they had surely been unearthed together at Pompeii, said I was scaring off the birds. Good! What flesh-eating avians must have been lurking in those foreign trees! Tigris had not the wit to be perturbed by the noise. This clanking came from the damned—forgive me—harpoons.

Since Sydney-town, I had borne the burden of two harpoons; the newest Technology, I had been told, American in design, with a single flue and a soft shaft, quite unlike our antiquated English kinds. Whatever the meaning of all that was, I did not know. What did I know of harpoons? God confound Confusion! And God confound the card game in which I had won them. Better that I had lost! For, I had discovered, no one wished to buy American harpoons, and they are jolly cumbersome. Not only this, but they had also served to distract me from my great Purpose there in the colonies.

To look at me, the idle observer would be forgiven for not immediately divining that I was a man with a Grave Mission, as I went along on my stupid horse with my hideous Contraptions of harpoons. And yet it was so.

The invisible flesh-eating birds coughed and cackled from within the trees.

I was tired.

I wished to remain honest.

The previous night, I had got some advice from a sailor which I took rather to heart, because he looked very much like Richard III and had therefore an air of natural authority about him. I cannot recall the name of the public house in which I met him, but I can report it was of dubious cheer, peopled by Specimens of a kind I can hardly describe. It cannot have been more than forty years old, for that was the age of the colony, and yet its beams and boards had the black smoke-and-grog pickling to them that only the inns of greatest antiquity achieve at Home. It was in this institution that I was compelled to secure lodging for myself and my pair of American harpoons, a storm of exceeding inconvenience having descended upon the town as we docked, and the inn being nearest to hand. I had intended to pay a visit to the nearest Bank immediately upon arrival, in order to draw funds against my letter of credit, but the storm had so delayed us that night had fallen when at last I descended to the terra firma of Hobart-town.

I had but little baggage, having been unfortunately divested of many of my trappings in Sydney through a confluence of mischance and my own poor judgement. My reduced accoutrements were now quite manageable by hand for a short distance, even with the harpoons. I put my head down against the torrent and ploughed through the storm towards the dim and oily light of the inn.

My evening there had begun indifferently with a meal of gristle unencumbered by beef and a glass of oleaginous vinegar that could scarcely remember the vineyards of Italy (although it did rather evoke the Mediterranean coast, for there was a kind of gritty stuff collected in the bottom of the cup, like sand). I took this repast at the table nearest the hearth with the harpoons propped beside me, whence they first drew the eye of a Jezebel who approached and asked me in quite an ordinary way why my harpoons had such an odd look about them.

She was young, with interesting dark eyes and a neck so long it looked like she had survived a hanging—perhaps she had. She told me she had worked amongst sailors and whalers for five years and had seen a great deal, but never such queer-looking harpoons. We then embarked upon a very civil conversation on the topic of my harpoons, which expanded into a rumination upon the trade of whaling itself, and did not conclude until the young woman seemed to remember herself and, with a half-heartedness that was not encouraging, offered to meet me in a private place for a certain sum. We were interrupted by the sailor I have mentioned, the one with the look of Richard III, hunchback and all, who hobbled forth to say, ‘Sally, be off with you, for this is an honest place.’

‘My name is not Sally, Jack.’

‘All such girls as this are called Sally,’ he said to me.

‘And all such men as you are called Jack,’ said she to him.

The sailor conceded that he was, in fact, called Jack, and the girl withdrew, telling me she would not stay where she was not welcome, and that her name was Maria Regina, after the Virgin, and went bare-armed and bare-headed out into the storm.

She had seemed perfectly honest to me, and I do not think my own intentions had been dishonourable. It is true that I am quite easily led, and I had enjoyed conversing with a young person with interesting eyes and a half-hanged neck, and who paid me a morsel of attention, for I was quite alone in that place. But I was loyal to my dear Susannah, I told myself, and would be worthy of her.

I carried with me the memory of love as a little shadow in my heart. If I were in a cheerful mood, this shadow of love bolstered me, but when I was downhearted and lonely, it gave me nothing but more questions.

The sailor cast his attention to my harpoons, and briefly I thought I might have found a buyer at last. But to my sorrow, his interest only went so far as to examine and expound upon every flaw in their design.

‘Indeed, I am encountering some difficulty in selling them,’ I told him.

Leaning against the bar, so as to ease his humped back, he told me that I might divest myself of them for a fair price at a whaling-station, if I were to go in person to visit such a place. There I might find a Customer with the most immediate need and the independence (if an harpooner) to select and purchase his own weapon. He should also have the disposition to do so, if he were employed by a whaling-station that paid a commission, by whale, and I were able to convince the harpooner of the superiority of my devices. That sounds more trouble than it is worth, I said. Yes, it is, said the man. And what is a whaling-station? I asked. He laughed and gave me up for useless—as I certainly was. I paid for his ale.

Before the great burden of the harpoons had come upon me, I would have used this interchange to ask the sailor Richard III if he had any news or knowledge of the woman whom I had travelled across savage oceans from England to rescue. What distraction! Two harpoons and I did not even think to mention her name.

I resolved to do better.

There was a great fireplace in the tap-room with a fire ablaze within, which may sound somewhat like cheer, but, in short, was not. The fire hissed and spat like an indignant Cat from the rain leaking down the chimney, and what little warmth and comfort it may nevertheless have provided was rather dampened by the conceivably human figure piled into a chair before the hearth. This personage’s head and face were entirely subsumed by great profusions of perplexing hair and was—the Hair or the Man, or both—emitting a most extraordinary aroma. He so blocked the fire’s effects that I remained wet from the storm, although I had been as near the hearth as I could for above two hours. All that reached me was a thick and cloying smoke.

The Person before the fire did also succeed in rather gaining the upper hand—conversationally, I mean—by speaking at all, that being so unexpected from such a Creature. As I withdrew from the sailor, harpoons over my shoulder and gristle in my teeth, the figure in the chair produced a mouth from amongst the hair and said, ‘Come now, man, do not look so downcast.’ What can one say to simple kindness from a stranger? It shoots straight to the heart of a vulnerable person.

The fire picked out two twinkling grey eyes amongst his hirsute visage.

‘How did you come by those irons?’ he asked.

‘What irons?’ I asked. ‘Forgive me, sir, I do not know to what you refer.’

‘Your harpoons, man,’ he said, with a smile. ‘Where did you find them? I find it difficult to imagine that you intentionally have bought them yourself, for—and I hope you will fo

rgive the presumption—you quite clearly have nothing to do with the whaling industry.’

‘Ah—yes. As to that, I won them in a card game.’

‘Bad luck!’

‘Thank you.’

He nodded very civilly. ‘There is a commodious whaling-station a day north-east of here,’ he continued. ‘It is known as the Montserrat Station, and it is renowned for its black oil.’

‘Indeed?’ I said, for want of something better.

This remark caused the hairy man to smile, though I did not perceive why.

‘Indeed. I am employed there, and I will return to-morrow. Why do we not go together, man, and find safety in company on treacherous roads? And when we are there, I will introduce you to Mr Heron, who is the Station-Master, and he will perhaps purchase your irons. Or, if he does not, I shall introduce you to one or another of our harpooners, who may wish to purchase your goods directly—especially young Jackie, who seems to have a head for Technology. At any rate, no matter which person is or is not interested in your harpoons, Mr Heron might perhaps also extend to you an offer you may wish to entertain. That is, you might buy the station yourself, as Mr Heron has an ill wife and wishes to give up the business. He will sell at a loss, I am certain, for his wife will not dwell in Hobart-town without him—she says it is too rough—and so she lives under his protection in a place greatly rougher, which is not conducive to her health, although, in my opinion, the air there is the finest and freshest in the world. And I have breathed the air of ten continents, so I am well placed to make the judgement.’

I did not know if he had forgotten he was addressing me directly, for he was gazing ruminatively into the flames as he spoke, and showed no signs of not launching into the story of his life and all his ancestors. The man was Irish, as I determined from his voice, and I did have it upon good authority that the Irish on this Isle were all Cannibals. Although, I must admit, the young Maria Regina with the black eyes had also been Irish, and she had not seemed a flesh-eater. And the Personage before me seemed more and more a Man as he spoke, and less a pile of putrid and hairy rags. He shifted his position, and I saw he had a great canvas sheet about his shoulders, which he dropped to the ground. With this impediment gone, he stood, and presented quite an ordinary appearance, but for the hair, and the bare feet. A pair of bedraggled boots steamed upon the hearth behind him. These contributed, I think, to the general malodour. This olfactory offence lingered, but we are imperfect creatures, we humans, and I forgave.

A Treacherous Country

A Treacherous Country